The inflation battle continues

- Mark Greenwood

- Dec 8, 2025

- 4 min read

Mark Greenwood, Deputy CIO at Atlantic House Investments, discusses our relationship with inflation and its enduring impact.

For most of the past two decades, inflation seemed tamed, an artefact of the 1970s, studied in history books rather than lived in daily life. Then came the pandemic, supply-chain chaos and war in Ukraine, and prices once again leapt into double digits. Central bankers have since claimed victory, but it would be hasty to assume the battle is won. Inflation tends to vanish quietly, only to reappear when least expected.

After all, the economic conditions that once anchored prices (cheap global trade, abundant energy, disciplined fiscal policy) are looking fragile. The world may not be heading for hyperinflation, but neither should anyone assume a comfortable 2% will always be the norm.

The “rule of 70” offers a sobering calculation: divide 70 by the annual inflation rate to find how many years it takes for the value of money to halve. At 2%, purchasing power erodes by half in 35 years. At 5%, it happens in just 14. For anyone living on a fixed income, pensioners in particular, that difference is ruinous.

Financial markets care because central banks do. Inflation dictates interest rates, which in turn drive the value of bonds, shares and property. On an ordinary day, a ten-year government bond might move by a fraction of a percentage point. When new inflation data is published, volatility doubles. The monthly inflation figure is, quite simply, the heartbeat of modern markets.

Investors in rich countries tend to treat low inflation as a birthright. Emerging economies have long known that it is a privilege. From 2010 to 2020, prices rose on average by 5.3% a year in South Africa, 5.9% in India, 6.2% in Brazil and 9.5% in Turkey (Source: IMF).

These differences reflect not only economics but institutions. Rich economies enjoy independent central banks, credible courts and reliable statistics. Many developing countries do not. But the line between the two is blurring. Ageing infrastructure, overburdened energy grids and political pressure on central banks are becoming more common in advanced economies. It is no longer unthinkable that inflation in places like Britain or America will experience more frequent bouts of inflation above 5%.

Inflation itself is a statistical construct, and how it is measured can shape the debate. Britain’s old Retail Price Index (RPI), still used for some bonds and pensions, tends to overstate inflation because it does not accurately account for substitution effects. For example, if the price of beef goes up, people may buy cheaper chicken instead. The Consumer Price Index (CPI), used by most central banks, is more consistent internationally. From 2030, RPI is expected to be replaced by CPIH, a variant of the CPI that includes housing costs.

Even the modern CPI has quirks. Central banks focus on “core” inflation, which excludes food and energy prices because they are volatile. That makes sense for policymaking, but some may feel it is detached from everyday life. Surveys by the Bank of England show that consumers care most about food and petrol prices, the very categories omitted from the official target.

Each household, in truth, faces its own inflation rate. A student, a young family and a retiree spend on entirely different baskets of goods. For one, rising tuition costs may dominate; for another, rent or medical expenses. No single index captures these differences perfectly, which is one reason inflation is as much a psychological phenomenon as an economic one.

Inflation data is among the most transparent statistics in economics: the underlying prices of milk, petrol, electricity, and thousands of other items are publicly available. In Argentina, where the government once manipulated its inflation numbers, private trackers quickly revealed the deception. Independent researchers, such as those at MIT’s “Billion Prices Project,” were used to reveal true inflation trends and put pressure on official sources to be more accurate.

Beyond official statistics, markets themselves reveal what investors believe about future inflation. Britain offers a particularly rich example: about a quarter of its government bonds are “index-linked,” meaning their returns rise with inflation. Comparing their yields to those of conventional bonds gives a “breakeven rate”, the inflation level that would make investors indifferent between the two.

At the moment, the breakeven rate for ten-year bonds hovers around 3%. In other words, investors expect prices to rise by about 3% a year over the next decade. Central banks watch this number closely. Even more revealing is the so-called “five-year, five-year” measure, what the market expects inflation to average over the five years, starting five years from now.

This figure captures long-term credibility. During the recent inflation surge, Britain’s five-year, five-year rate barely budged, implying that investors trusted the Bank of England to restore stability. Had it climbed much higher, towards 4%, the Bank would have seen that as a warning sign that confidence was slipping and its credibility was being questioned.

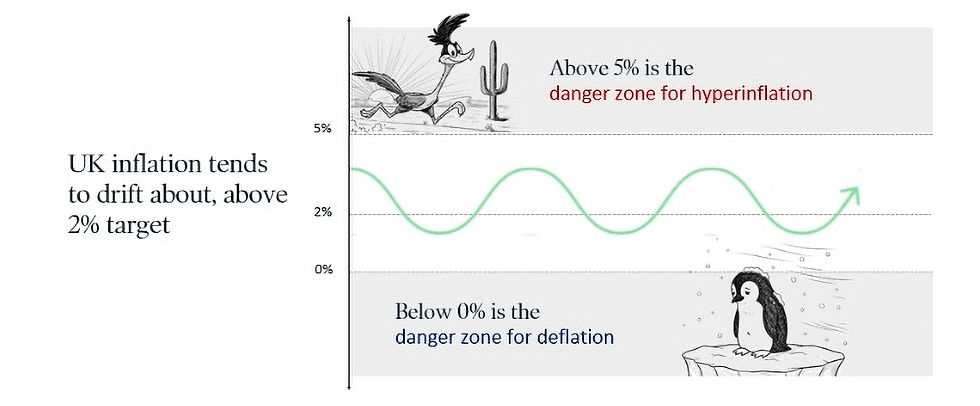

Inflation, like temperature, has a comfort zone. Around 2-3%. Economies run smoothly: prices rise enough to encourage spending and investment, but not so much as to distort them. Below zero lies the frozen world of deflation, as Japan discovered during its “lost decades.” Falling prices discourage consumption and trap economies in stagnation.

Above 5%, the opposite occurs. Economies “run hot”: wages and prices chase each other upward, and long-term planning becomes impossible. Restaurants reprint menus monthly; firms cannot forecast costs; savers flee to hard assets. Once inflation escapes its comfort zone, bringing it back can require punishing interest-rate rises and a sharp slowdown, precisely what the world endured after 2021.

Economists are expected to forecast inflation, but history suggests many are not much better than a coin toss. A study conducted by Atlantic House, which examined economists’ forecasts on Bloomberg, found that only a handful of forecasters consistently outperformed the market. Markets, by contrast, aggregate the views of thousands of participants who must back their opinions with real money. Their expectations, distilled through prices, are often the best guide available.

Modern inflation forecasting, therefore, relies heavily on market signals. Inflation will never disappear, nor should it. A small, steady rise in prices keeps an economy running smoothly, but too much destabilises it. The trick for central banks is to keep expectations anchored, close enough to the target, so that people and companies can plan effectively.

As long as market measures such as the “five-year, five-year” stay near 2-3% we can feel comfortable. When those expectations drift higher, it is a sign that faith in monetary authorities is fraying. In the longer term, inflation is heavily influenced by sentiment and confidence in the ability of central banks to contain inflationary pressures.